HAFT CINEMA IV

AFTER IMAGINARY WEIGHTS AND TRANSPORTED PRESENCES

programme

VISUAL VARIATIONS ON NOGUCHI Marie Menken | 1945 | 4 min

WATER MOTOR Babette Mangolte | 1978 | 8 min

UN JOUR PINA A DEMANDÉ [ONE DAY PINA ASKED] Chantal Akerman | 1983 | 57 min

total runtime: 69 min

Writing for the New York Herald Tribune in August 1943, Edwin Denby expresses a conflict: ‘the motion picture is the only means of accurately recording dancing, but dance lovers are aware of how rarely it projects anything like the dance quality one knows from the theatre.’ The great American dance critic constantly announced the inadequacy of filming stage dance. He lamented the choices forced by a camera’s field of vision: one cannot capture the entire stage and minute details in the same frame – a problem only amplified when multiple dancers feature, and close-up shots must highlight one (or some) at the expense of the other(s). He complained that crucial architectural context is always compromised on film, and suggested that to film a dancer at too close range is to diminish for the audience the mystery of her art: ‘they are embarrassed to see her work so hard.’ (The same close range, he concedes, makes Fred Astaire’s subtler style better suited to camera than the ballets Denby cherished.) For the critic, that a filmmaker must decide when to shoot up close and when from afar, was nothing short of a catastrophe:

When a stage dance has been photographed from various distances and angles and the film assembled, the effect of the dance is about like the effect of playing a symphony for the radio but shifting the microphone arbitrarily from one instrument to another all the time.

In a later essay, ‘Forms in Motion and Thought’ (1954; revised 1965) Denby captures the central ephemerality of the art he celebrated: ‘they dance and, as they do, create in their wake an architectural momentum of imaginary weights and transported presences. Their activity does not leave behind any material object, only an imaginary one.’ Dance relies on an accumulating wake of gestures which hang in the air and the mind. Film – and so filmed dance – is a similarly durational medium, for which accumulation of images is the defining element. But where a precise movement passed in space is afterwards irretrievable, it is the nature of film to be revisitable; for that which at first passed across our screens to later repeat unchanged, should we so wish. What results is an especially vexing dynamic between the mediums. This programme presents a trio of dance films which are each, in their own way, intimately engaged with the problems Denby raises.

We begin with a film that does not so much depict a dance, but which is one: Marie Menken’s Visual Variations on Noguchi (1945). So apparent is Menken’s concern with sensation and embodiment in Visual Variations that P. Adams Sitney identifies in it a ‘Whitmanesque fascination with the body,’ despite no persons appearing on screen. Indeed, for Menken, filmmaking is primarily an ecstatic movement experiment:

There is no why for my making films. I just liked the twitters of the machine, and since it was an extension of painting for me, I tried it and loved it. In painting I never liked the staid and static, always looked for what would change the source of light and stance, using glitters, glass beads, luminous paint, so the camera was a natural for me to try, but how expensive!

Among Denby’s recurring complaints is that ‘the camera gives a poor illusion of volume; it makes a distortion of forshortening and perspective, and it is plastic only at short range’ – which precise qualities Menken exploits in articulating a vision of Noguchi entirely her own. As the title of Will Heinrich’s 2024 New York Times review of the film, ‘Seeing Isamu Noguchi Through Someone Else’s Eyes,’ attests, Visual Variations dives headfirst into the full subjective potential of filmmaking. Shot almost entirely in close-up on a 16mm Bolex, the film embraces everything Denby found objectionable about filming dance. You never see any Noguchi piece in full; rather, you are plunged by dizzying handheld glimpses into Menken’s vision of the work. Originally silent, the film is enriched by a strange, striking soundtrack composed by Lucia Dlugoszewski and added in 1953.

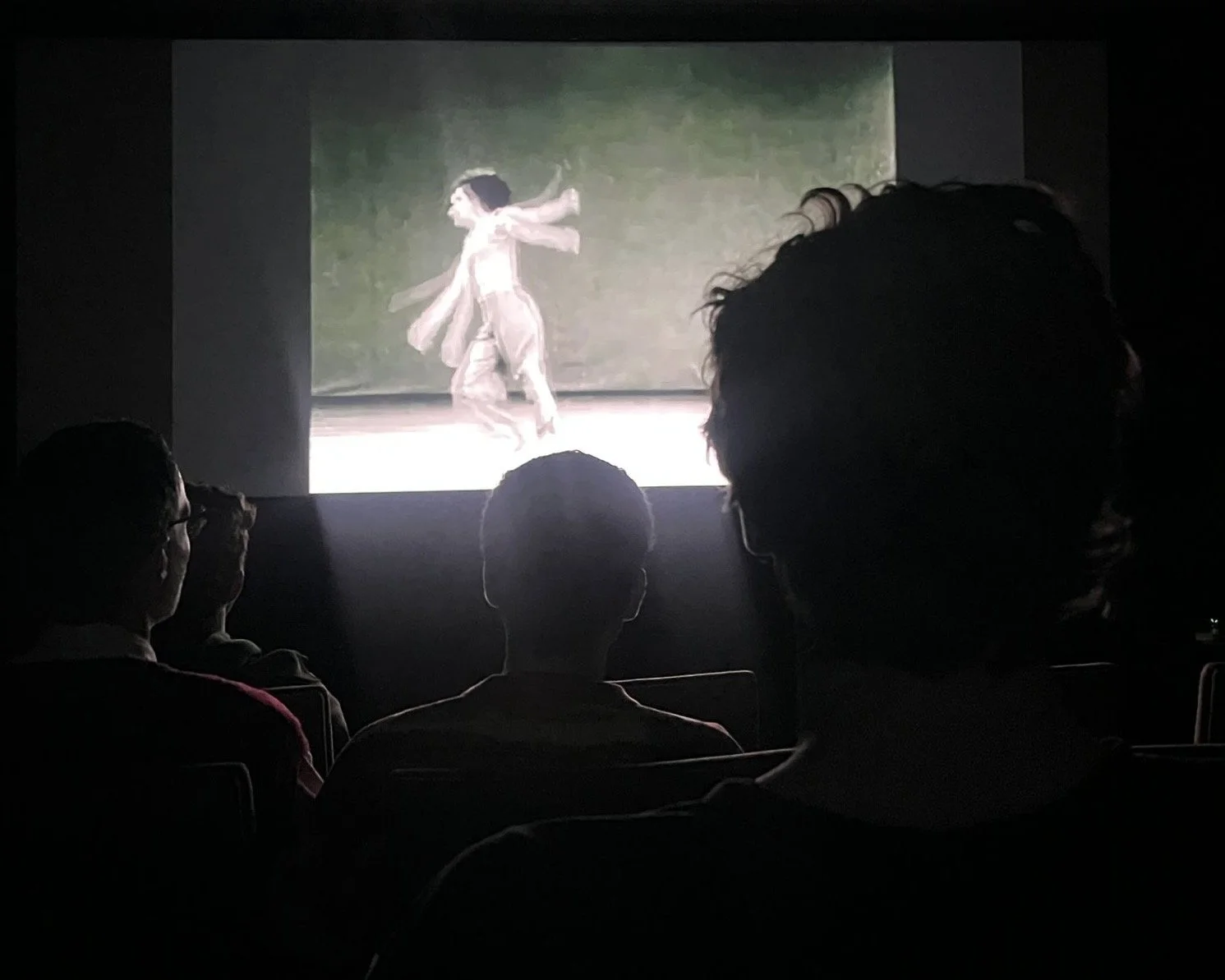

Water Motor (1978) instead seeks to exploit the camera’s imagined potential for objective documentation. The resulting film is a silent, forensic study of Trisha Brown’s eponymous solo, shot from a static position, with only subtle panning from left to right (to ensure the dancer’s body stays in frame). The film shows the titular solo in its entirety, twice. First, in real time, then, immediately afterwards, in slow motion – 'to understand it better and but also to see something you can’t see any other way,’ according to director Babette Mangolte.

Mangolte – whose alertness to the camera’s negotiations with perspective I discuss in an essay for Sabzian – shares with Denby a striking resolve against varied camera positions in the filming of dance (and a recognition of the particular photogenicity of Astaire’s style). In a 2017 essay on the making of Water Motor, she writes:

I knew that dance doesn’t work with cutting and that an unbroken camera movement was the way to film the four-minute solo. I had learned it by watching Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly’s dance numbers. Somehow the film camera has to evoke the hypnotic look and total concentration of the mesmerized spectator and fragmenting the solo in small pieces taken from different camera positions would break the spectator’s concentration and awe.

In preparation to shoot Water Motor, Mangolte first visited Trisha Brown’s loft several times to learn to dance the solo herself. So much so does Visual Variations concern only Menken’s personal vision of the work that Noguchi was not even present when she shot it in his Greenwich Village studio. The two shorts present opposing responses to the paradox Denby identifies: that film is the best hope of objectively documenting movement, and by nature an irretrevably subjective medium. A useful if imperfect analogy for the approaches Mangolte and Menken take can be found in the long debate between word-for-word and interpretive translation practices. Following this analogy (just one step further), our programme’s feature can be understood as part translation, part translator’s diary.

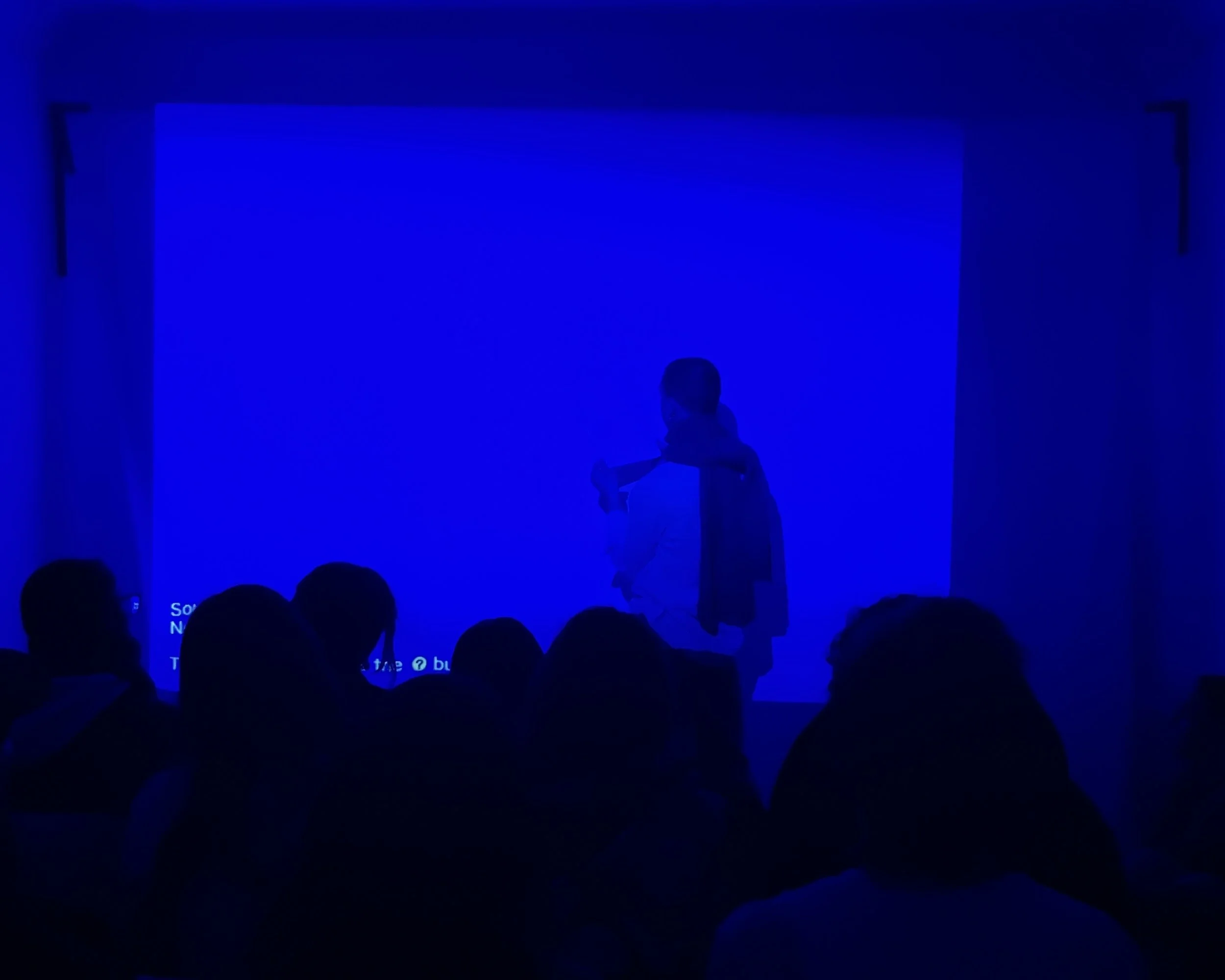

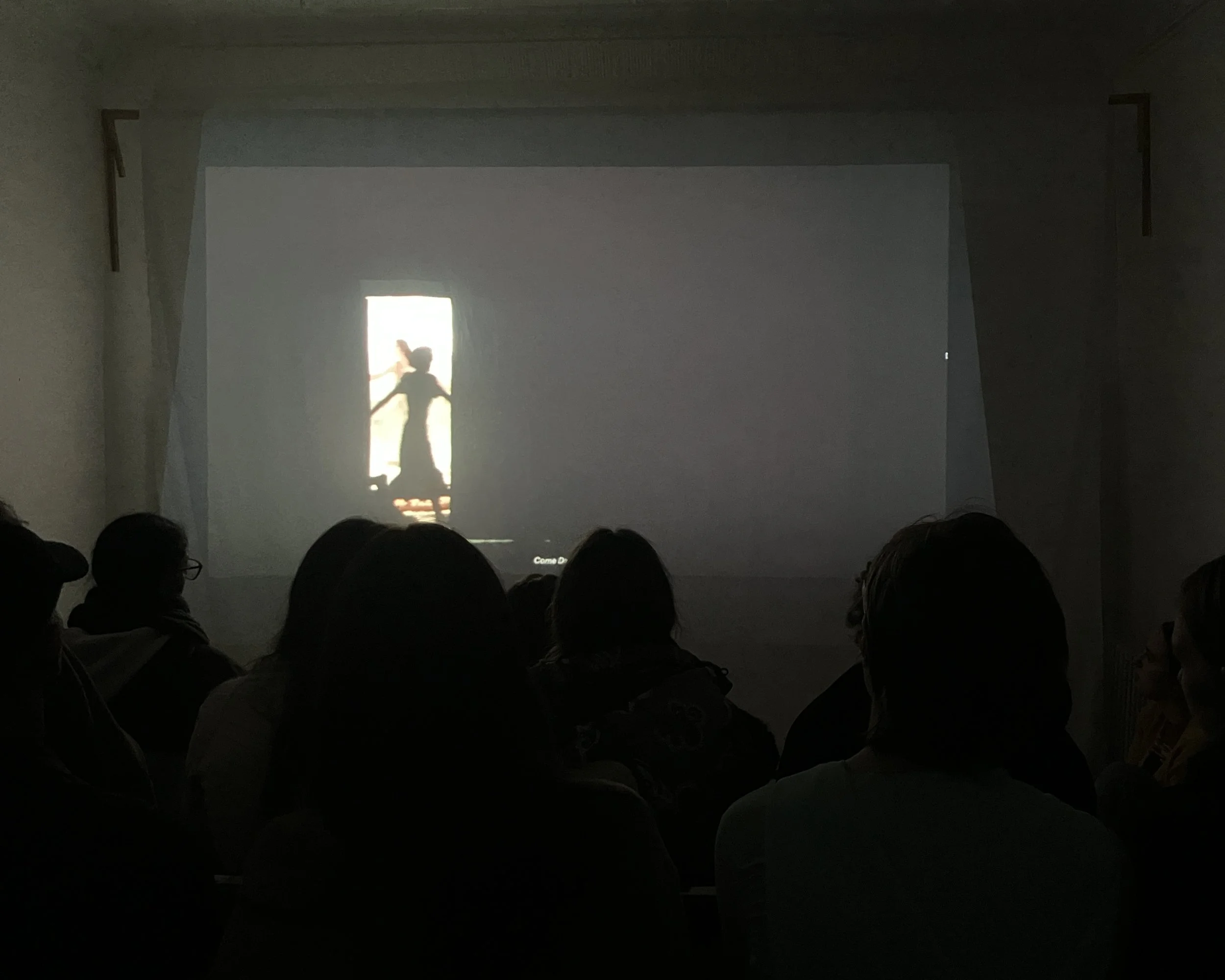

Chantal Akerman’s sensitivity to the challenge of filming dance pulses beneath her compact documentary, Un Jour Pina a Demandé… [One Day Pina Asked] (1983). The film opens on a hand-holding, ringing dance viewed only partially, through a doorway from another, darkened room. The shot recalls those Victorian-era optical toys which play on the persistence of vision – thaumatrope; phenakistoscope; zoetrope – surfacing the perennial challenge of capturing motion. As we glimpse the distant circling dance, Akerman confesses in voiceover: ‘J’ai le sentiment que les images que nous avons ramenées en transmettent peu et les [performances] trahissent souvent.’ [I feel as though the images we brought back convey little, and often betray [the performances]].

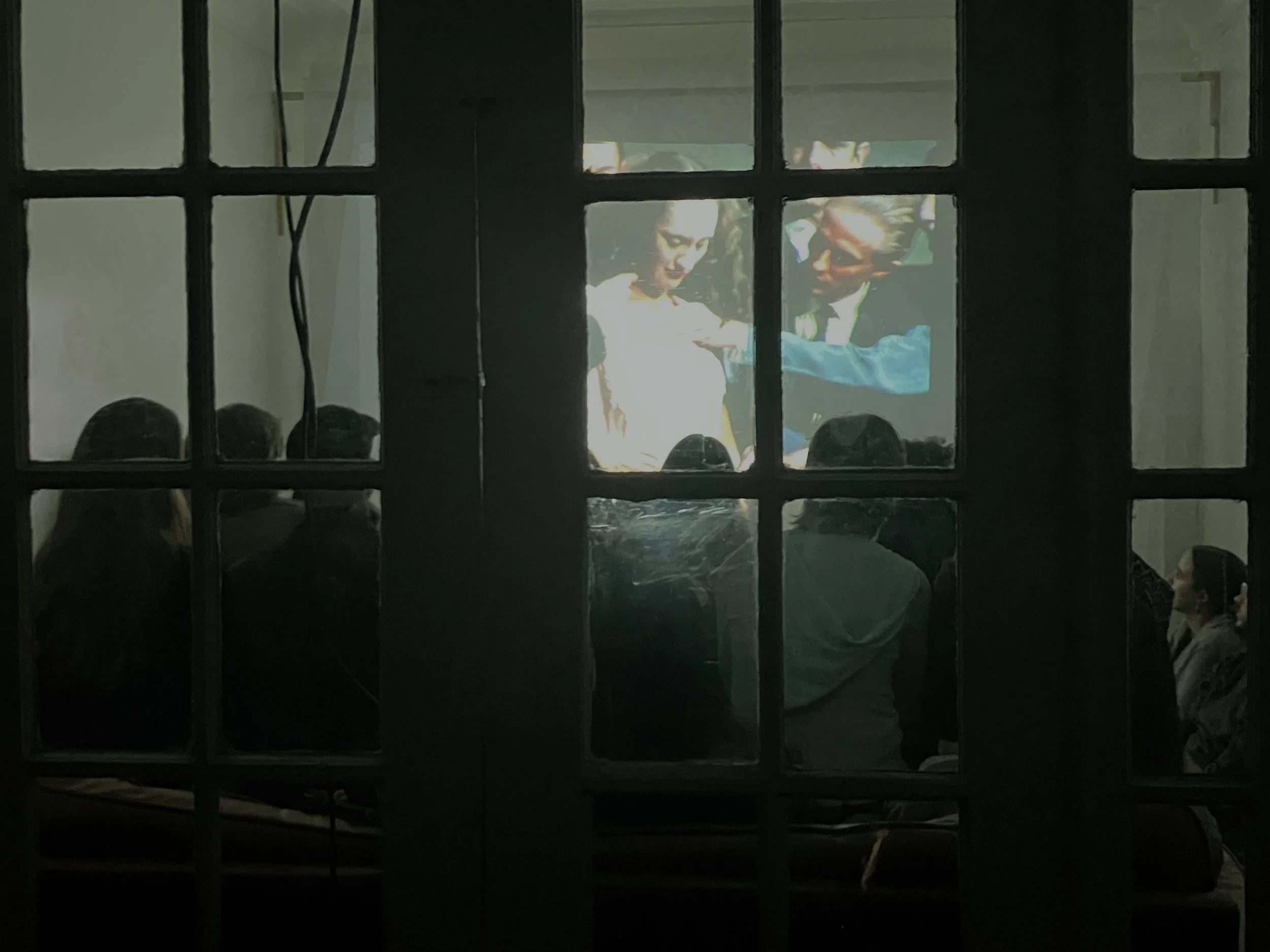

Originally commissioned for the French television series Repères sur la Modern Dance [Landmarks of Modern Dance], the film follows Pina Bausch and her dancers on tour in the summer of 1983. It is comprised of backstage glimpses of dancers applying lipstick; rehearsal footage, and talking head interviews, interspliced with long excerpts of performances of the following iconic pieces: Come Dance With Me (1977); Kontakthof (1978), 1980 (1980), Walzer (1982), and Nelken (Carnations) (1982). We see Nelken in particular evolve to reach its newly complete form at Avignon’s Palais de Papes. Akerman’s fascination – and frustration – with capturing the works persistently hums throughout. At one point, we see the director sitting on the floor of a small bedroom, describing her experience watching the company:

Il y a vraiment eu des moments où j’ai senti que je devais me défendre de ce qui était exprimé, que à des moments de ce spectacle, j’étais obligée de fermer les yeux. Et en même temps, je ne comprends pas pourquoi.

There were truly times when I felt that I had to defend myself from what was being expressed. Moments in the performance when I had to shut my eyes. But at the same time, I don’t understand why.

Having seen Pina, one gets the feeling. Elsewhere, Edwin Denby articulates his fundamental qualm with filming dance thus: ‘[a camera’s] field of vision is totally unlike that of a theatre seat.’ (Dance Magazine, October 1954). The films presented in this programme exploit and defy that idea, circling the possibilities of its meaning.

—

January 14, 2025

THE BENCH COLLECTIVE

@the_bench_collective

London, England

February 12, 2026

SOFTCORE CINEMA CLUB

@softcorecinemaclub

Oxford, England

January 29, 2026

ARTS LETTERS & NUMBERS

@artslettersandnumbers / www.artslettersandnumbers.com

Averill Park, NY, U.S.A

February 20 2026

INTERROBANG 11232

@interrobang11232 / www.interrobang11232.com

Brooklyn, NY, U.S.A

February 1, 2026

YORK UNIVERSITY

w/ live performance by Harry Clarke

@duh_vani / @harrybyharry

Toronto, Canada

February 19 2026