HAFT CINEMA II

No Dead Nature: Still Life with Moth, Flower, and Spit

programme

MOTHLIGHT Stan Brakhage | 1963 | 4 min

THE GARDEN OF EARTHLY DELIGHTS Stan Brakhage | 1981 | 2 min

CHINESE SERIES Stan Brakhage | 2003 | 2 min

STILL LIFE [طبیعت بیجان] Sohrab Shahid Saless | 1974 | 90 min

total runtime: 98 mins

[Les fleurs sont gaies et brillantes, ou tristes et ternes; elles s’agitent sans cesse, quoique presque imperceptiblement, se tournent vers la lumière, s’écartent pour laisser passer des branches perfides, s’infléchissent sous l'influence de la sécheresse, se gonflent et s’épanouissent sous la caresse d’un rayon. Les fleurs ne sont pas de la nature morte! Il n’y a point de nature morte. [...] Tout agit et réagit dans le tourbillon continu de l'univers. Tout est à la fois une chose et un être, une œuvre et un ouvrier. Il n’y à point de nature morte!

[Flowers] are gay and brilliant, or sad and dull; they move ceaselessly, albeit almost imperceptibly, turning towards the light, parting to let perfidious branches pass through, bending under the influence of drought, swelling and blossoming under the caress of a ray. Flowers are not still life! There is no still life [...] Everything acts and reacts in the continuous whirl of the universe. Everything is at once a thing and a being, a work and a worker. There is no still life!

— Théophile Thoré, ‘Musée de Rotterdam,’ Musées de la Hollande (1858-60)

Thoré, the 19th-century French art critic best known for ‘rediscovering’ Vermeer celebrates nature’s continual motion, and urges its relevance in thinking about art which seeks to represent life. In the Rotterdam Museum chapter of his extended survey of the Netherlands’ art museums, he struggles against the French term for the genre known, in English, as still life: ‘nature morte’ [lit. dead nature]. Inanimate objects engage the echoes of life around them, and the flora in these paintings are inextricably part of the natural cycle of renewal. For Thoré, ‘nature morte’ writes out the life that sings through these paintings. His quarrel with the term encourages us to consider the perpetual thrum of life in our making and thinking about art. Haft Cinema’s second programme screens Sohrab Shahid Saless’ Still Life (90min, 1974), preceded by three brief shorts by Stan Brakhage: Mothlight (3min, 1963), The Garden of Earthly Delights (2min, 1981) and Chinese Series (3min). These are brought together for their embrace of ‘le tourbillon continu de l'univers’ [the continuous whirl of the universe], and their engagement with the project of representing it.

Let us move first to a pressing issue of translation: the original-language title of Still Life, (and Farsi term for the same genre of painting) is ‘طبیعت بیجان,’ which translates most literally to ‘lifeless (or inanimate) nature.’ This splits the difference conceptually between the Romance language terms (which translate literally as ‘dead nature’) that Thoré resists, and the Germanic equivalents, all iterations on ‘still life,’ (originating with Dutch ‘stilleven’). The gradient of conceptual implications across these terms, which imagine the subjects of these works as variously dead; lifeless; or still, forms a rich landscape from which to move into our consideration of the film henceforth referred to as Still Life.

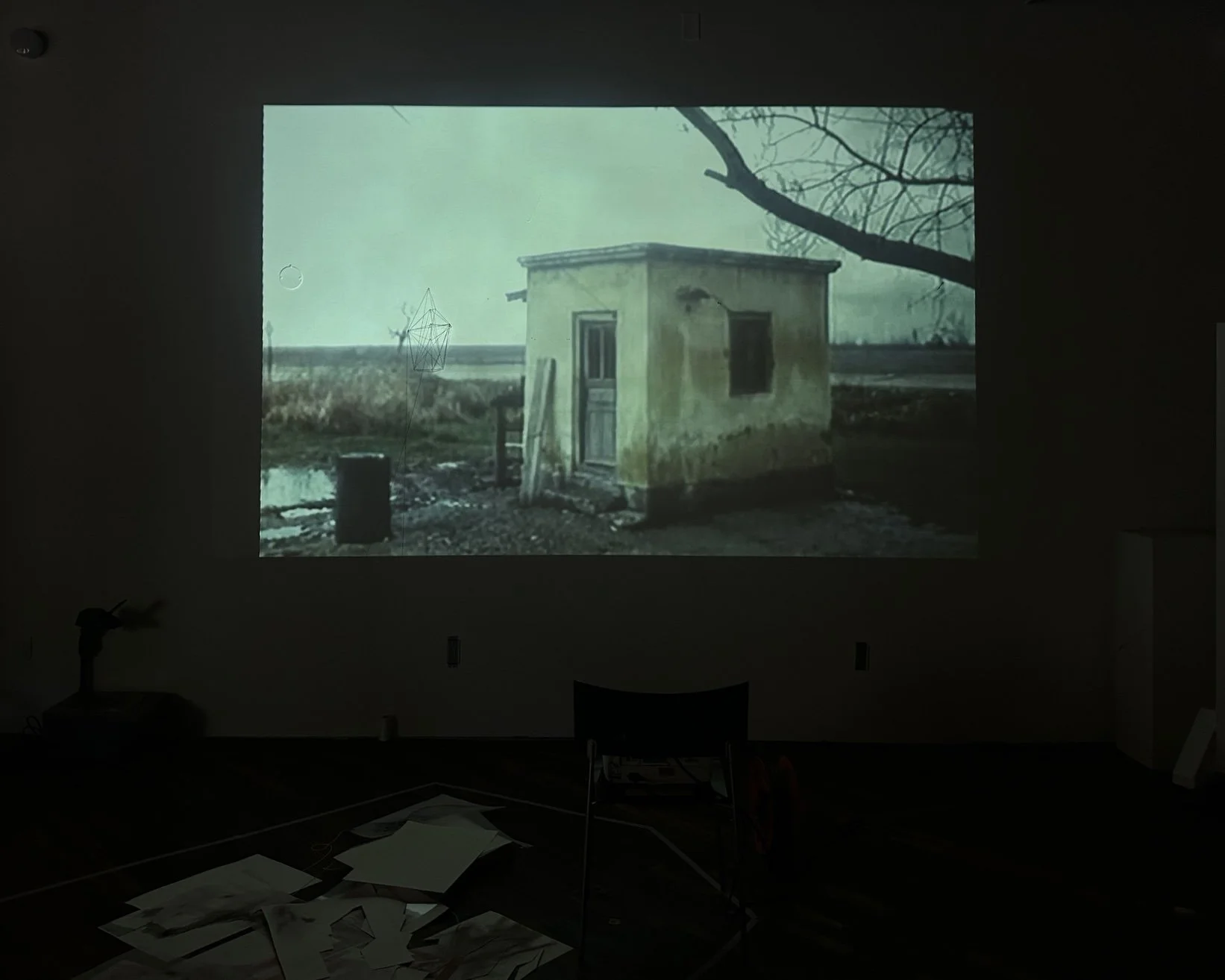

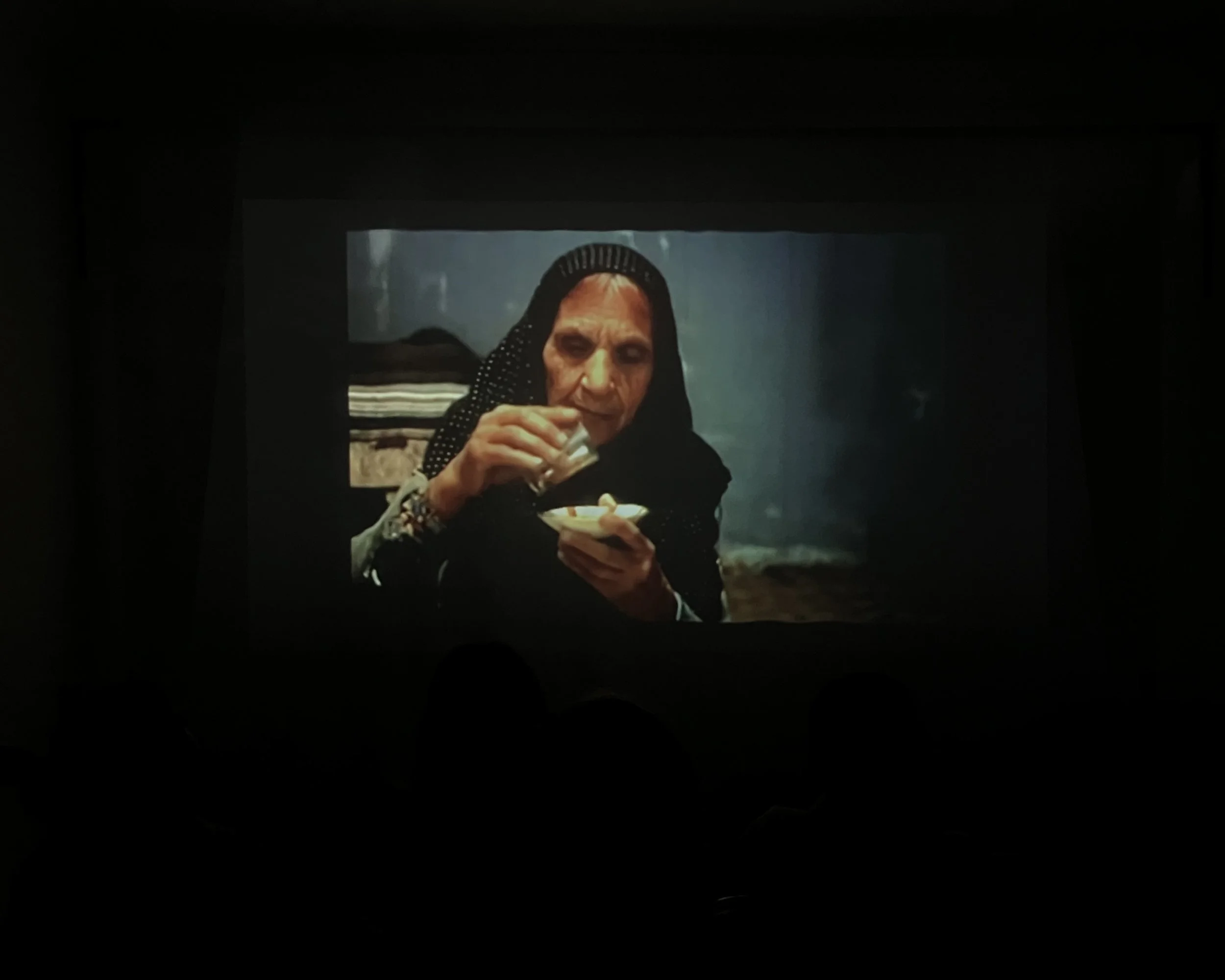

Still Life follows the routine of Mr Sardari, an aging railway switchman in rural Iran. Sardari is numb to the imperceptible aliveness of the universe that Thoré describes. When asked his age, he can give no definite answer: ‘نمیدانم. نمیدانم والا’ [I don’t know. Really, I don't know]. All he is able to recall with certainty is how long he has worked his post: thirty-three years. Over the ninety minutes of Still Life we watch Sardari smoke 5, perhaps 6 cigarettes, though he seems to take no pleasure in this. Nor, despite coughing terribly, does he seem to register his own discomfort. One begins to feel that the cigarettes are smoking him; such is the extent of his resigned detachment. Dialogue in the film is sparse, and the few conversations that take place often repeat. Early in Still Life, Sardari’s wife asks him to purchase sugar for the household. Twice in the next twenty minutes, she asks if he has done so, and twice comes the reply: ‘یادم رفته’ [I forgot]. It seems as though in the Sardaris’ lives, nothing ever changes.

Yet all around them, Iran is changing. In another early scene, we watch a herd of sheep slowly cross the desolate railroad junction where Sardari is stationed, and are reminded that his solitary days are taking place as a largely agrarian society underwent rapid economic and infrastructural change — often leaving rural people behind in the process. State abandonment and repetitive labour render Sardari’s days near-indistinguishable. Events loop continually: over and over, we see him go to the railway junction, return home, return to the railway station; again and again, we watch him decant tea from his estikan (teacup) into his nalbaki (saucer). Repeatedly, and ironically, we see him wind and rewind his clock (here, I notice with delight that ‘tourbillion’ [whirl] also refers to a clock escapement). Mr Sardari is not (merely) forgetful; he is hostage to a memoryless existence.

Towards the close of Still Life, Mr Sardari is given a retirement notice. Stunned, and in the knowledge that this will devastate the family’s barely-viable finances, he continues to perform his duties, even after a new station attendant arrives to replace him. Eventually, with no welfare system in place and no means of supporting his family, Sardari goes into town (on train that has passed him by for decades) to speak to the heads of the his company. When he finally arrives at the bosses’ office, they simply tell him to go away. For a while, he just stands there, looking on in silence as the company heads are served tea — which arrives with plenty of the sugar Mrs. Sardari keeps hoping her husband will remember to buy. The heads of the train company reminisce over a box of old photographs, and discuss upcoming weekend plans, ignoring Sardari, for whom no such past — or future — exists. When they eventually recall Sardari’s presence, they once again tell him to leave, and he goes. This is the quiet culmination of years of not-happening.

Still Life’s title, while describing the stasis pervading Sardari’s existence, of course alludes also to the genre of painting Thoré discusses, which takes objects as its subject. Attending to the objects in Still Life, it emerges that against an otherwise muted colour palette, missed opportunities to enter the changing world arrive in screaming blue. The train that passes each day is light blue; Mrs. Sardari’s sewing box, a hinted but inadequate means of financial emancipation, appears inlaid with turquoise. When the Sardaris’ son, on leave from military service, visits for one night, he comes in the door carrying a shocking blue messenger bag. This bag, at first tucked away by Mr. Sardari, but later opened by the son, is revealed to contain two oranges, bringing much-welcome sweetness and colour to the household. This collection of blue objects suggests scuppered hopes of change. They hint towards the continual motion which persists, even if the Sardaris have been too long crushed under the ambient strain of futile efforts to fully perceive it.

***

Stan Brakhage’s three shorts respond to the same ontological questions Still Life approaches, while forming a counterpoint to Saless’ manner of representing the real. As its title implies, Still Life is mimetic and realist in its approach; performances are understated, and moments drift, pass, and recur in long, static shots. Mothlight, Garden, and Chinese Series — all three, silent films made without the use of cameras, embrace life’s perpetual motion while overturning basic assumptions of mimetic representation altogether.

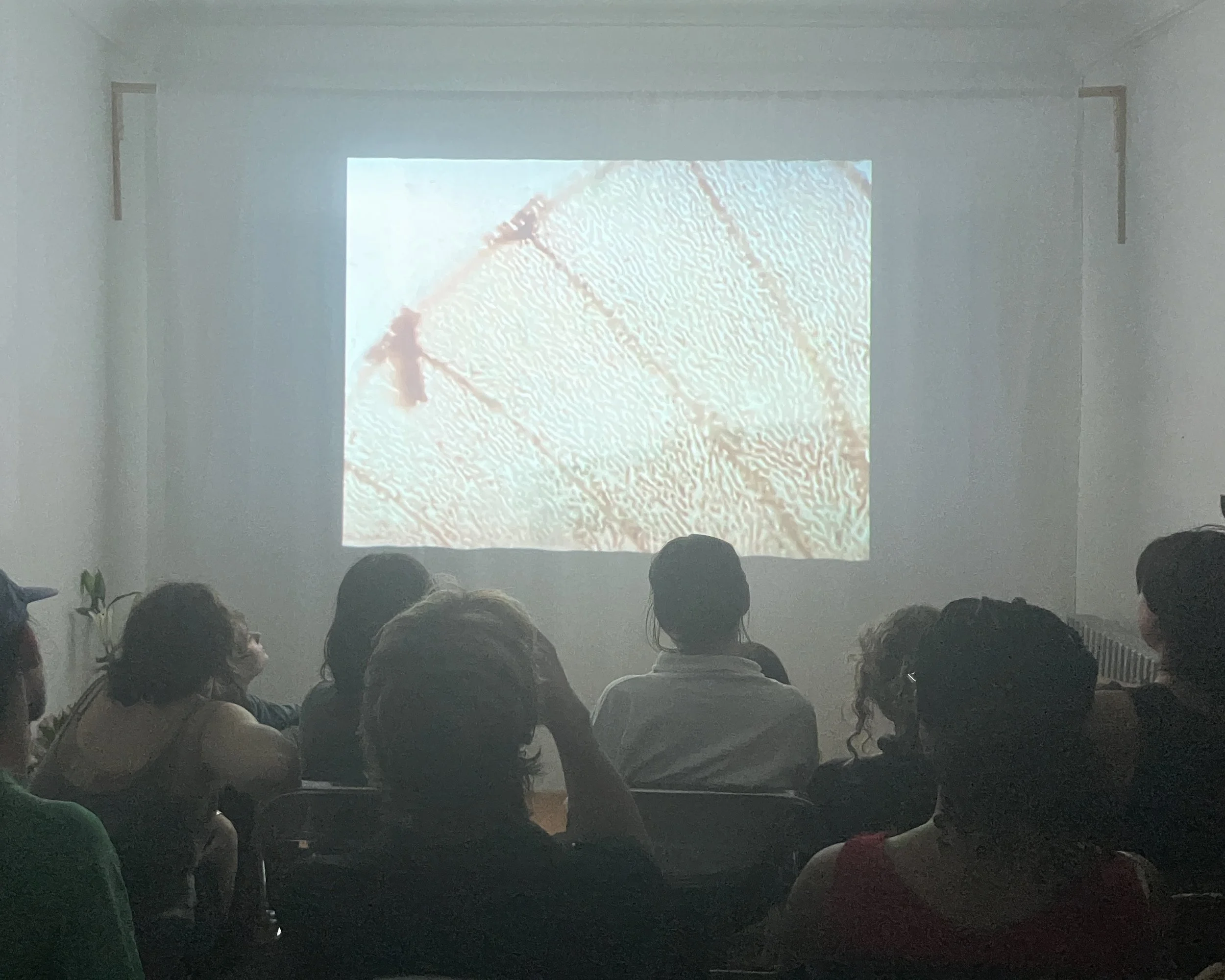

Mothlight and Garden are assemblages of pieces of the natural world. Brakhage made Mothlight by collecting dead moths, leaves, and seeds, and pressing them between two layers of 16mm sprocketed mylar.† When fed through a projector, light filtering through exposes the intricate structures of the moth wings. Where Władysław Starewicz — the ‘original dead-bug filmmaker,’ if you will — reconstitutes dead insects into representational puppets, Brakhage uses insect remains as the material substance of Mothlight. When he made the film in 1963, he was living under the ‘great despair’ of oppressive financial strain, unsure of how or where he would find the money to feed his five kids, but continuing, obsessively, perhaps self-destructively, to make films. In a 1999 conversation with Bruce Jenkins, Brakhage describes seeing moths flying towards lightbulbs and into candles, and identifying with them, thinking: ‘this is what’s killing me, is my love of the light,’ until, ‘suddenly, I couldn’t stand the thought of that going to waste, these lives, in vain.’

Nearly twenty years later, Brakhage returns to the Mothlight technique with 35mm tape to produce Garden. He calls it an ‘homage to (but also an argument with) Hieronymus Bosch,’ presenting a collection of flora that alludes by colour to the triptych for which it is named. These are silent films, but to see them (in original format) is to listen to the whir and sputter of a film projector breathing voice into these creatures. Mothlight and Garden play at the boundary of ‘dead nature,’ vivifying remnants of the natural world by the projection of light, and by the appeal to an audience’s sustained attention. These films readily embrace ‘le tourbillon continu,’ while challenging mimetic representation with material presence.

The same is true of Brakhage’s final work, Chinese Series. ‡ He worked on Chinese Series through the last days of his life, softening black 35mm film emulsion with his saliva, and scratching it with his fingernails. It was to be released at whatever state it reached when he died. Chinese Series troubles various boundaries: as Fred Camper writes, its ‘exploding lines flirt with the depiction of recognisable objects.’ Being made by his scratching and of his spit, the film embodies Thoré’s assertion that everything is at once ‘une œuvre et un ouvrier’ [a work and a worker]. Above all, Chinese Series cries out, ‘I am still here,’ continually, and began to do so only once Brakhage was no longer.

All three Brakhage shorts in the HC-2 programme announce and recognise that moths, flowers, and filmmakers too are continually drawn ‘vers la lumière’ [towards the light], for worse and for better.

***

Through the final act of Still Life, the frame increasingly lingers over objects in the Sardaris’ home: a simmering pot on the cusp of boiling over, Mr Sardari’s cap hanging from the wall, his eyeglasses resting on the windowsill. This stock-taking culminates with the film’s closing scene, when, forced to move out of their house, the Sardaris collect all of their belongings onto a cart outside. The displacement is devastating. But, seeing the Sardaris’ effects gathered under the bleak light of day, one is reminded of H.D. Thoreau’s method of cleaning house. When he had to scrub the floors at Walden Pond, he would carry all of his things outside. Of seeing all his possessions gathered in nature, Thoreau writes:

It was pleasant to see my whole household effects out on the grass, making a little pile like a gypsy’s pack, and my three-legged table, from which I did not remove the books and pen and ink, standing amid the pines and hickories. They seemed glad to get out themselves, and as if unwilling to be brought in. I was sometimes tempted to stretch an awning over them and take my seat there. It was worth the while to see the sun shine on these things, and hear the free wind blow on them; so much more interesting most familiar objects look out of doors than in the house.

The resonance this has with the image at the close of Still Life is one of form, not circumstance: Thoreau’s gesture is voluntary; the Sardaris’ is not. If Thoreau’s act revels in playful affirmation of freedom and self-reliance, the Sardaris’ results from a sudden overturning to their stilled existence, out of their control. But in each, as a total collection of belongings hits the open air, we glimpse possibility — even if, in the Sardaris’ case, only of what might have been. Thoreau’s words also evoke Brakhage’s emphasis on unfamiliar method for throwing into relief the perpetual aliveness of the turning world, and for celebrating our participation in it.

Thoré’s resistance, in the midst of his book about Dutch museums, against the term ‘nature morte’ opens onto the plethora of questions concerning the artist's relationship with ‘le tourbillon continu de l'univers.’ In thinking about life’s humming through everything, the films in the HC-2 programme do not offer platitudes. Rather, through opposite representational approaches, they hold on to a common truth: Brakhage, who writes in 1991 that film ‘must give up all that which is static, so that even its stillnesses-of-image are ordered on an edge of potential movement,’ faces us with this edge by eschewing mimetic representation for material presence. Saless, for his part, impresses upon a viewer that even in the slowest of films; even in the stillest and most devastated existences, life goes on. Omnia Mutantur; Nihil Interit.

—

July 01, 2025

† For a more detailed explanation of this process, see: Toscano, M. (n.d.) ‘The Garden of Earthly Delights’ Lightstruck.

‡ His ‘final work’ is not entirely straightforward to identify. It was ‘supposed’ to be Panels for the Walls of Heaven (2002), but, being in the indefatigable relationship with filmmaking that he was, a few more came before his death in March 2003; Chinese Series is named for a (frankly vague) resemblance Brakhage saw between his scratchings and hanzi.

BELSYRE GARAGE Oxford, England. July 10

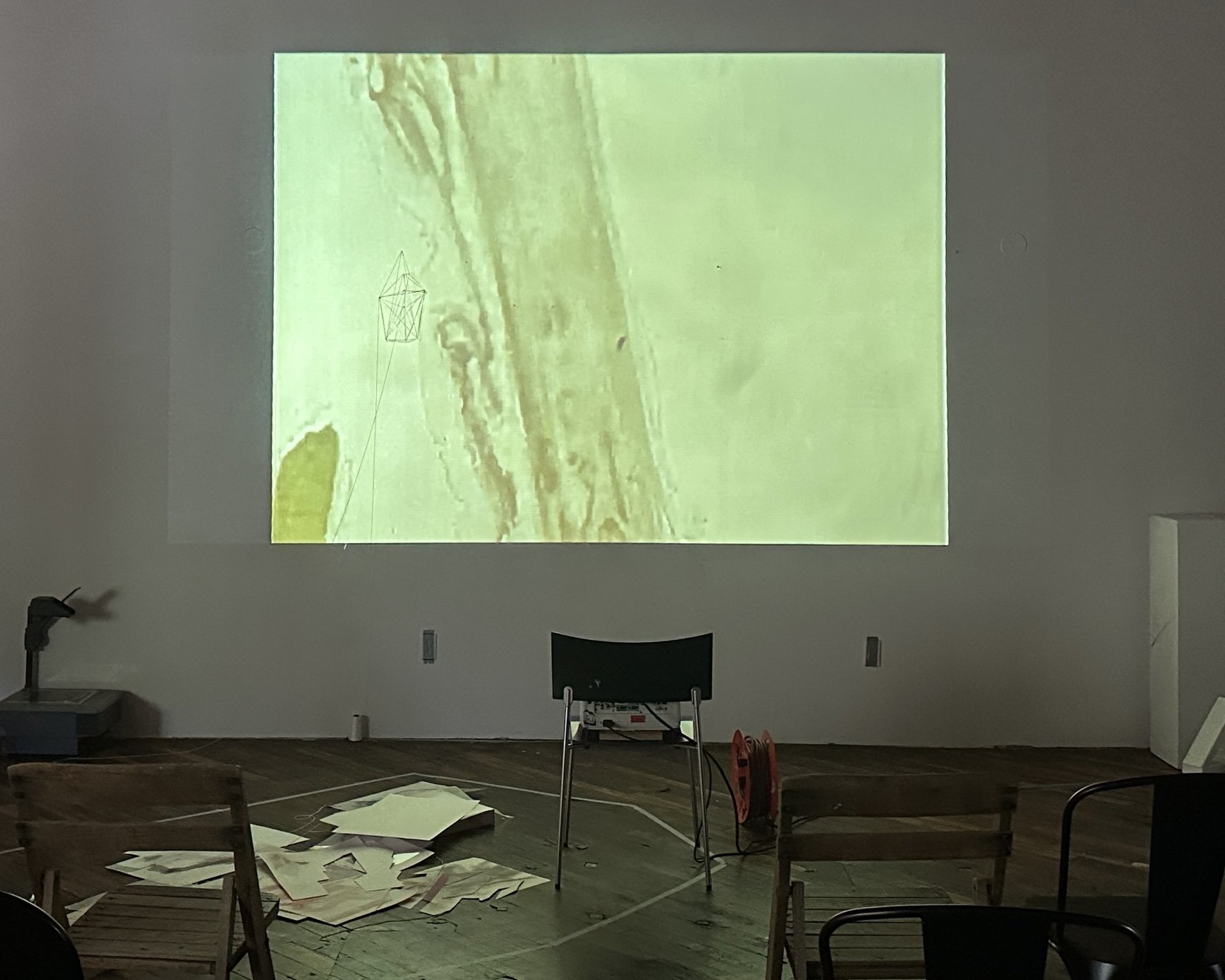

Works-in-progress by Maisie Goodfellow & Tom Hodges-Gilbert decorated the Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies’ Belsyre Garage, while diaphanous fabrics and paintings served as window coverings, ensuring the screening room was appropriately darkened. A pink bruiseface, painted by Maisie prior to the screening on what would later become the projection wall, serendipitously punctuated the films.

ARTS LETTERS & NUMBERS Averill Park, NY, U.S.A. July 20 2025

A screening took place in Arts Letters & Numbers’ main studio space, which that week was also the site of Recitations of a Drawing by a Place-Bonder, a workshop led by Bahar Avanoğlu & Ipek Avanoğlu. Works-in-progress from the workshop ornamented the room, including a string installation by Saam Shojaie, pinned on what would become the projection wall. Saam’s work acted in conversation with questions at the heart of the programme, and echoed Maisie’s bruiseface across the Atlantic. A rich discussion followed.

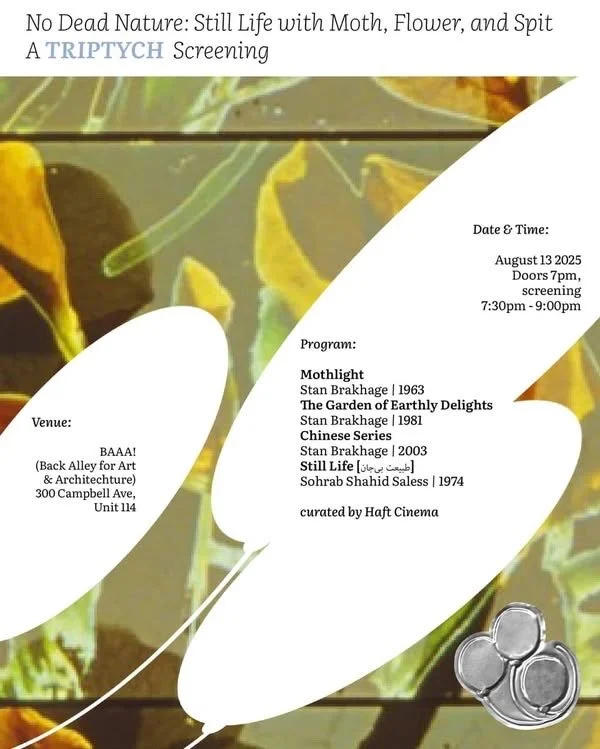

BAAA! by TRIPTYCH Toronto, Canada. August 13 2025

The curatorial collective Triptych (Melina Sabeti-Mehr, Kt Sullivan, and Dhvani Ramanujam) organised a screening held at Reza Nik’s experimental arts and community space, BAAA! The event featured an installation of Shannon Garden-Smith’s In a hare’s form V (2021), at once an ode to Brakhage’s films and the lighting fixture illuminating a dedicated reading nook, where audience members were invited to peruse archival materials from Jane Wodening's scrapbooks and the HC-2 Toronto Booklet, by Triptych. Persian sweets and tea were served.

INTERROBANG 11232 Brooklyn, NY, U.S.A. August 30 2025

On a late summer evening at Jacksun Bein’s project space Interrobang 11232, fresh and dried flowers lined the walls either side of the projection screen. Jacksun read the programme essay before the films began. The main space (full to capacity) was supplemented with an additional space, splitting the audience between theatre-style viewing and an ad-hoc pillows-and-rugs set up in the next room. Following the screening, homemade toast, eggs, and roasted red pepper gazpacho prepared by Eero were served.

THE GARDEN South London, England. August 31 2025 [private screening]

Andy Deng & Mika Konishi Gaffney hosted a private garden screening in South London. In delightful counterpoint to the themes of the programme, fruits from the garden were served, bringing a fitting close to the season.

APPENDIX

In his obituary for Brakhage, P. Adams Sitney derives seven principles from Stan Brakhage’s Metaphors on Vision (1960). These are appended here, as they are enumerated in the obituary.

‘(1) the eyes are always moving, scanning in response to all visual stimuli; (2) vision never stops; the eyes see phosphenes when closed, dreams when asleep; (3) the names for things and for sensible qualities blunt our vision to nuances and varieties in the visible world; (4) normative religion hypostatizes the power of language over sight (“In the beginning was the word”) in order to legislate behavior through fear; (5) the self-conscious and responsible use of language is poetry; (6) only through an educated and comprehensive encounter with literature can a visual artist hope to gain release from the dominance of language over seeing; there can be no naive, untutored vision. (7) the artist is repeatedly challenged to sacrifice the gratifications of the ego and the will to the unpredictable demands of his or her art.’